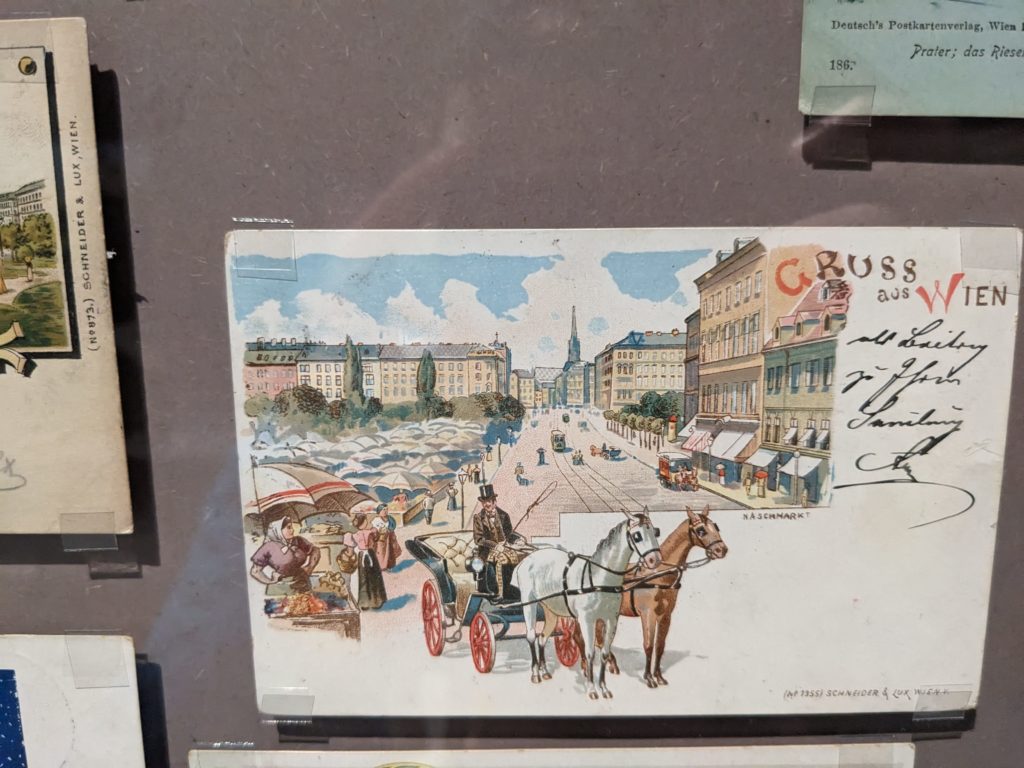

The late 19th Century and early 20th Century saw a huge craze for sending and collecting postcards. There was a thrill to pictures arriving in the mail, giving a glimpse — highly idealized and likely doctored — of another city or country. It was an aspirational outlet for a rising middle class. Evidence of it remains, if you look in the right places. For example, in Joyce’s Dubliners in the story A Mother, Mrs Kearney has her daughters participate in all manner of improving activities: “Kathleen and her sister sent Irish picture postcards to their friends and these friends sent back other Irish picture postcards.”

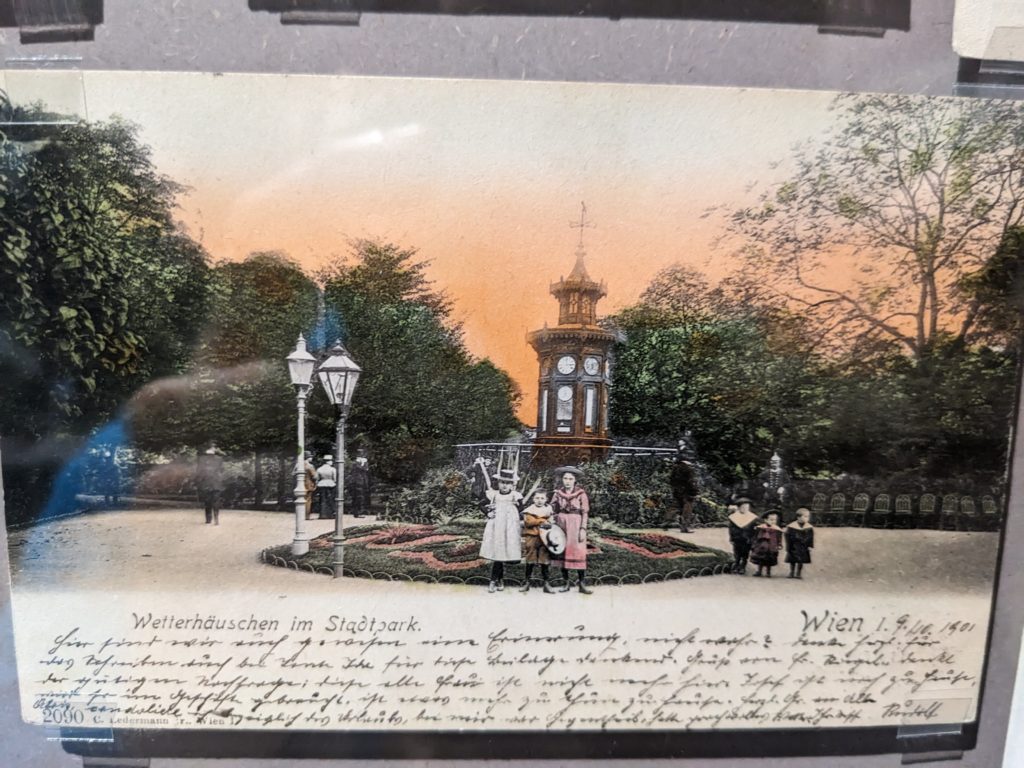

Letters had existed, but, as we continually learn, pictures and especially photographs have a broader, more powerful appeal. Pictures can be eloquent in ways our words fail to be. This isn’t me diminishing our writing. The Wien Museum’s excellent postcard exhibition informed me that it wasn’t until recently that anyone bothered transcribing and studying the messages contained in the vast corpus of vintage (ie old) postcards. It is part of the universal human condition to scrawl dull cliches on the back of a postcard. There are few keen observations or witty aphorisms. But occasionally when a war happens, soldiers might write something down about life in a field hospital after narrowly avoiding being totally blown to smithereens. Gather up enough of those and you have something worth of study.

The exhibition ultimately concludes that instagram has inherited the mantle that postcards once held in our popular culture. This is most certainly true. It’s easy to be nostalgic for cursive handwriting and postage stamps; I myself have a perverse inclination towards sending friends postcards even when I can instantly message them with high resolution phone photos. You shouldn’t mistake nostalgia for cultural vitality. But if you need further convincing I encourage you to look at the colorization on some of these old postcards and try and tell me this doesn’t foreshadow the instagram filter.