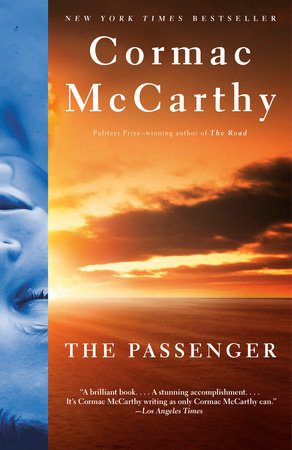

The Passenger by Cormac McCarthy

When critics talk about a writer’s “late style”, I have come to understand it as a euphemism for a writer losing their grip in the fundamental demands of the craft. Where once they had themes that would elevate a plot they now engage in philosophical crankery that leaves their stories obscure and inscrutable. The Passenger is fine example of this. It can be fairly described as ambitious without having to admit it doesn’t function narratively. Its prose can be praised without having to examine why it compares so poorly against the author’s earlier work. It is mystifying enough in its intent that few will dare call it an outright failure.

Robert Western is many things as a protagonist. He is a Renaissance man who mourns his deceased sister, dead now for over a decade. He once dug up a small fortune in gold from his grandmother’s basement and blew it all racing cars in Europe. He was a math and physics prodigy, but is unable to deal with the guilt of his father’s involvement in the Manhattan project. He now works as a salvage diver and frequents the dive bars of New Orleans. His desire for his dead sister was incestuous, but honestly I have no idea what that fact has to do with anything else in the book. And for all that he fails to captivate.

There is a plot. One night Western is called out to a dive on a plane crashed underwater. Nothing about the crash seems right. The plane is intact, the bodies have been underwater for days already, the pilot’s bag is missing, along with a navigation panel. Something sinister is afoot. Mysterious agents are in pursuit. It is possible that Western has seen too much.

This precis might suggest that there is momentum to the narrative, so I should clarify that there is not. As Western feels mysterious forces breathing down his neck, he goes about his day with a startling lack of urgency. The story unfolds as a sequence of encounters between Western and various characters, always referred to by a work nickname: Red, Oiler, Shaddam, Borman, Dogdick, Grenellan, Royal. These characters often arrive unannounced and with no relation to what I just described as the plot. One passage sees Western sit down with Asher and have an extended conversation about the history of quantum mechanics. You could remove the scene and it would not damage the shape of the novel at all. It is Asher’s only appearance. Shaddam bemoans the depravity of the culture with all the verge of a Substacker with at most two overlong posts in them. Borman is a drunk hiding out in the swamp, going to seed, and suggests that while Western isn’t a piece of shit, or a prick, or an asshole, he is probably some kind of fuck. Not a dumb fuck. Probably a sick fuck. Dogdick doesn’t actually appear. “Tell Dogdick I’m still alive and still crazy”, Borman says to Western.

I was happy enough reading most of these encounters. At some point it becomes clear that the initial suggestion of a plot was just a faint. This is not No Country For Old Men again, this is the book of Job. Bobby goes from one converstaion to another, wrestling with all the many and various ways we might conclude that “life’s a bitch”. Much more tiresome are the dream sequences (or rather the hallucinations), from the past, from the dead sister, where she is trapped in nonsense dialogues with a deformed character referred to as the Kid. They are a case study in all the reasons why dream sequences are bad. They are long, they are recurrent, they barely relate to the plot, and they are utterly infuriating to read. They are distinguished from the rest of the text by being set in italic text, so you can quickly skim ahead and feel your spirits sink at their approach.

At some point late in the book we are granted an extended explanation of why there must have been a second shooter with a high powered hunting rifle to blow the back of JFK’s skull out. I think I have some idea of how it relates to the ideas the book is playing with. But I mostly thought it was a really embarrassing case of what the critics call a writer’s “late style”.