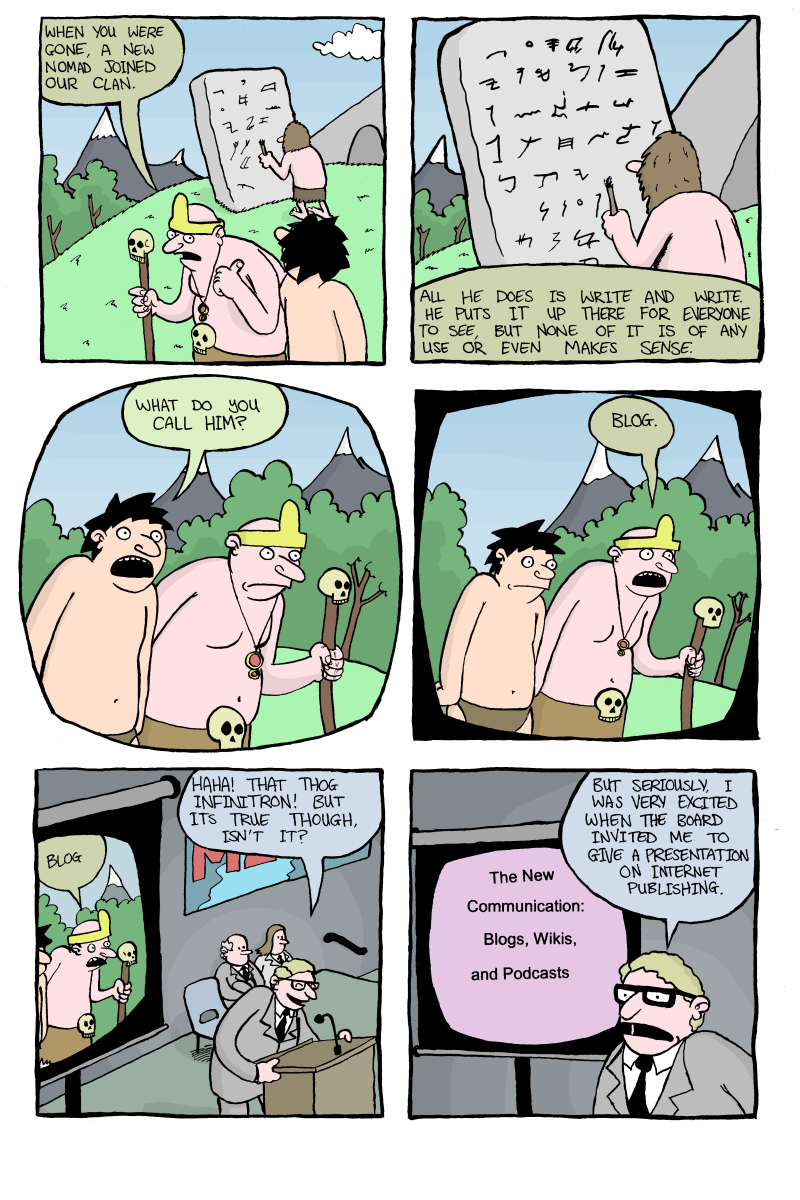

I only have myself to blame. I was the one who clicked subscribe on the Substack. I’m trying not to write a rebuttal; I’m not a fan of the “debate me” style of writing. And if you dunk on someone on Twitter and no one is around to like it, have you really dunked on them? If my current commitment to writing blog posts serves any purpose (and the consensus is that I am a decade too late to have a personal blog) then it is to organize my thoughts into something coherent, and maybe adorn it all with an appealing turn of phrase. I’d like to explain why what I read was so utterly disagreeable.

Erik Hoel is a neuroscientist, neuro-philisopher, and fiction writer. Recently, he wrote an impassioned Substack post addressing the “decline of genius”. Because, first of all, Erik Hoel believes in genius. Personally, I believe in “genius”, with the scare quotes, but I don’t want to derail my outline of Hoel’s argument this early. Erik Hoel believes, and asserts there is evidence, that the number of geniuses is in decline. This is despite an expanded education system and technological conveniences like powerful personal computers that we can carry about in our pockets. The golden age of human flourishing has not arrived, despite ostensibly perfect conditions. The cause, Erik Hoel believes, is that an old style of education — which he terms “aristocratic tutoring” — is the only reliable system that produces true genius, while the classrooms of today consistently fail to give their students that certain something. And with one weird trick, that is to say replacing classroom education with the one-on-one individual tutoring, we might yet reach a golden age, with a bounteous and reliable crop of little Einsteins, von Neumanns, and Newtons.

Hoel doesn’t simply want smaller class sizes or more resources. He advocates for intensive, rigorous, and engaging tutoring, done one-on-one. There is no compromise (or indeed much civic spirit) on the path to reliably producing geniuses. The education of John Stuart Mill is cited approvingly — Mill’s childhood was was a weird Benthamite experiment, designed to cram the classical canon into a child by the age of twelve, for no less a goal than to raise the future leader of a radical movement. Hoel neglects to mention Mill’s intensive education led to a psychological breakdown at the age of twenty.

There is no hiding the scorn Hoel seems to have for the efforts of the educators we do in fact have. The fact that there might be virtues to a public education system are not taken remotely seriously. But as frustrating as that is, I can merely dismiss it as wrong-headed and distasteful.

It is the genius stuff that really bothers me. The term “genius” is itself is so awfully weighted with elitist and reactionary agendas. Genius is more like a PR stunt than a genuine appreciation of human achievement. It is the convenient idea that Apple used to brand their computers — and not a serious was to engage with the history of science and ideas. You can say Einstein was a genius with absolute conviction and with little understanding of his theory of relativity.

It’s not that I don’t think that there are individuals whose talents and contributions rise above their peers. Your average tenured mathematician certainly deserves respect for their achievements, but for better or worse, there really are people who produce work on entirely another level. After roughly a decade in research mathematics, I can say that whether it be through nature or nurture, God’s gifts have been distributed quite unequally. (Appropriately enough, I appeal here to Einstein’s God).

And I simply don’t buy the idea that we have a shortage of geniuses. I think some people prefer to spout declinist narratives, tell educators that they are doing it all wrong, and dismiss contemporary art and culture and literature as being utterly non-genius. They prefer doing all that to appreciating the successes of today, simply because they don’t conform to some presumed ideal of genius.

It gets my goat because as I read the piece I can think of examples. To take what seems to me to be the example that should settle the debate: Grigori Perelman. Perelman’s proof of the Poincare conjecture in the early 2000s was a momentous moment in mathematics. Not in recent mathematics. In mathematics, full stop. His proofs arrived online without fanfare or warning. While it took time for mathematicians to process what he had written and conclude that a complete proof had been presented, they understood very quickly that it was a serious contribution. It is rather vulgar to say it out loud, and actually a disservice to the entire field of differential geometry, but you can rank it up there with any other seminal mathematical advance. It would be be bizarre to suggest that modern mathematics is impoverished when such work like is being produced.

That is just one example. How long a list would you like? Should I mention the resolution of Fermat’s Last Theorem? Big math prizes handed out reasonably regularly, and I don’t believe there are any shortages of candidates. But maybe their contributions haven’t transformed the world in the way people might imagine “proper” geniuses might. Maybe the problem is that they never read their way through the canon before adolescence. Am I actually expected to entertain this line of thought while I have the privilege of such fine specimens of achievement at my disposal. But I sense that Hoel will simply explain that Perelman and the rest were lucky enough to receive some variation on aristocratic tutoring. Exceptions that prove the rule, and all that.

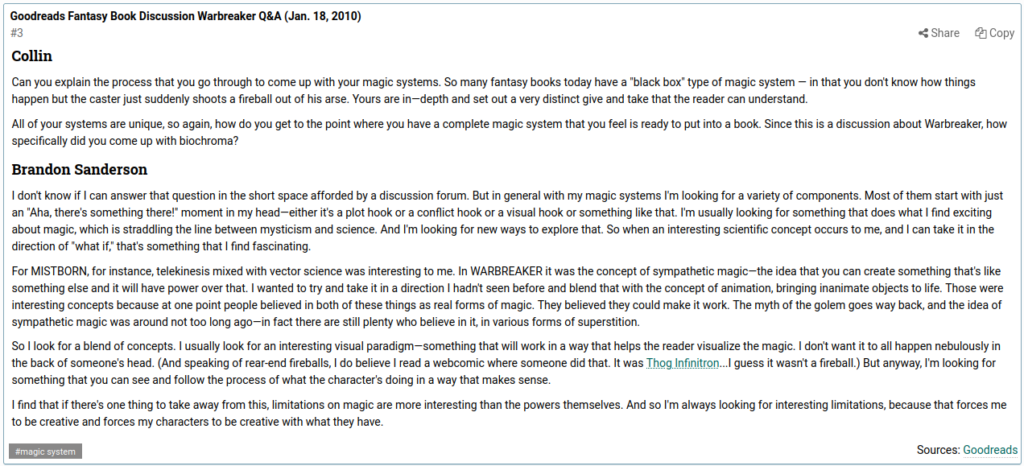

The whole business annoys me because instead of reading something that is interested in the human achievements that the essay claims to valorize, it wants to stack them up like shiny Pokemon cards to be measured by the inch. It aggravates me because I could be reading a New Yorker profile of someone who might not be a genius, but who is at least interesting. I could be reading the Simons’-funded math propaganda outlet Quanta which has the benefit of believing that there is great mathematics being done and that it is worth writing about. And most of all, for all the “geniuses” have done for the world, I’m still on team non-genius, and we still bring more than enough to the table.