New Hampshire’s state motto — Live Free or Die — struck me from the moment I first read it off a rear license plate as amusingly over-determined. Sure, the sentiment calls back to New England’s revolutionary tradition, but is now laden with so much other import that you have to laugh when you read it. Like with many other of the state mottoes I feel the need to ask “OK, but what are we really concerned about here?

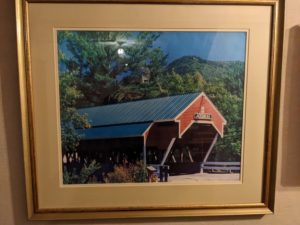

In the case of New Hampshire the answer to that question seems to be “covered bridges”. Which are quite literally what the name suggests. That is to say bridges built with their own roofs, preventing snow and ice accumulating on the road surface beneath. I am to understand that such bridges last longer, are safer to use, and attract an unusual degree of local pride. Based on the selection postcards available on the rack I perused, they are far prouder of their covered bridges than most of the White Mountain peaks. Driving past a particularly congested covered bridge we could see visitors slowing down to gawk and take photographs of themselves.

It’s all much less “Live Free or Die”, and much more “We Like Our Safer Bridges.”

The day after new year I went out for a jog around the small-town-liberal-arts-college-campus. With their leaves wet and glistening in sodden piles on the ground around them, the trees had the air of men who had thrown off their soiled garments and stood there completely exposed to the elements. They continued to hold up their branches — as dignified as they had been in their summer pomp.

One tree had been decorated in the fashion of a Christmas tree. I suppose we were still close enough to Christmas that this remained acceptable. Except that instead of the usual hung ornaments, baubles, tinsel and lights, the branches were laden with surgical masks, N95s, mini whiskey bottles, larger gin bottles, and the lids off tin cans, hanging by the ring pull. I imagine a student art project, or perhaps a particular kind of creative writing teacher trying to demonstrate the value of ritual and tradition, and the value of subverting it.

I jog by two kids throwing a blue American football back and forth while an adult supervised. They were wearing facemasks outdoors. I later pass a woman walking her dog and I began to sense a growing trepidation. Omicron was looming on the horizon.

I bought an LCD computer monitor for $25 on Craigslist and I’m feeling the thrill like it is 2002. The online listing site still lives, looking every bit like it is still 2002.

We drove across town to pick up the monitor, and I paid the man in cash. “I’m sorry, I just don’t like letting people into my house,” the seller told me as he led the way into his garage where he would demonstrate the monitor actually working before I took off with it. I told him that was entirely understandable, especially these days, but I realized his concern was not Covid related. After all, I was the only one of the two of us wearing a mask.

He was an older man, lean and wearing faded jeans and sneakers. His garage was tidy and well organized. The mind runs to dark and sensational places when a man explains that he doesn’t like letting strangers into his house. But these are usually the least interesting explanation for a man’s abiding attachment to his own privacy.

I just finished reading Lauren Hough’s collection of autobiographical essays Leaving isn’t the Hardest Thing. One of her more famous essays that appeared a few years back recounted her years working as a “cable guy” in a DC suburb. She often had to explain to customers that if they wanted their internet back, they were going to have to let her go down into their basements. “Unless you have kids in cages, I don’t care,” she would assure them. As she discovered, people have all kinds of reasons to be cautious about letting strangers into their home, many of them not actually sinister.