The 20th Century promised us flying cars, jet-packs, and Mars colonies. And how could it not deliver? It was already happening. The atomic age arrived, ending the Second World War in terrifying fashion, nuclear power was ushered in, and men walked on the moon. But where exactly did we fall short in achieving the envisioned grandeur of tomorrow? Was anything less than Star Trek going to be a disappointment?

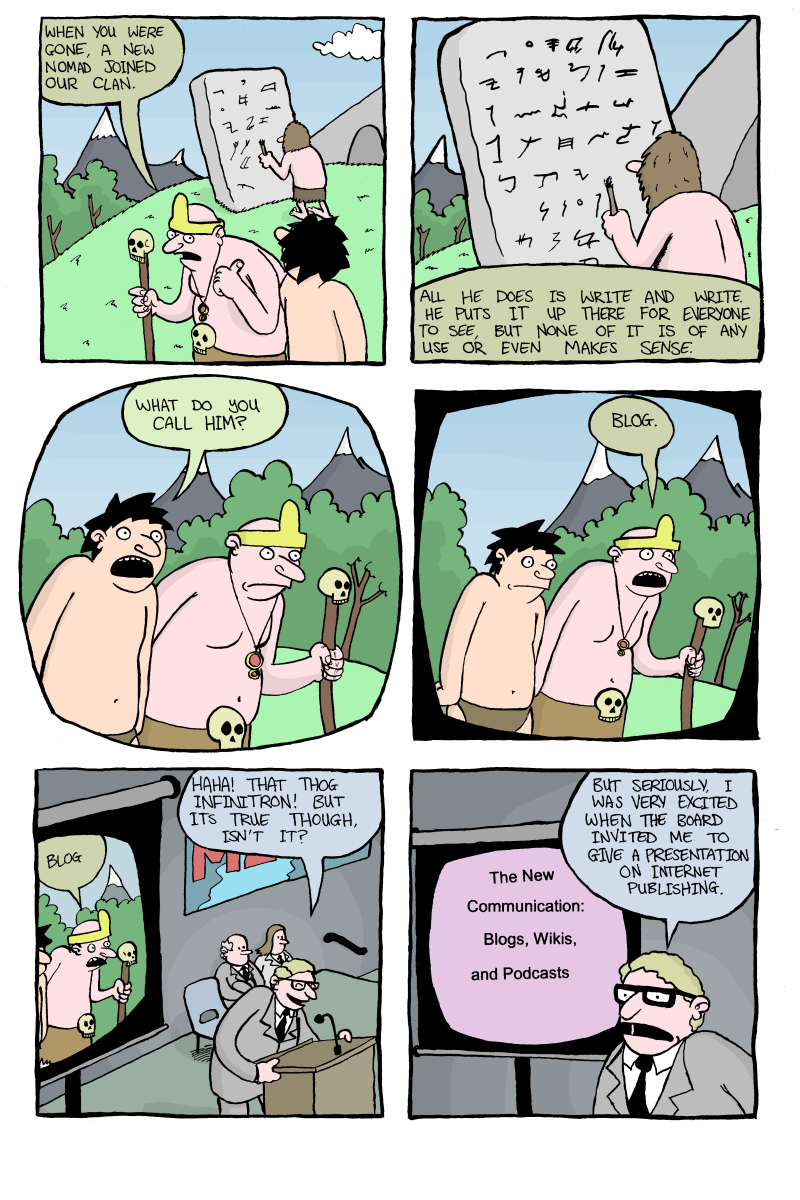

The 21st Century birthed a fresh litter of new promises and speculation; now it was the internet that was going to transform mankind. And how could it not deliver? The internet was already here. We were connecting and reconnecting via social networks, being blessed with the unlimited email inbox space, discovering with instantaneous search, guiding ourselves through meatspace via smartphone GPS, and abandoning TV for streaming. You have to separate the broken promises, and from those which became a nightmare.

One promise was of particular interest for those who, like me, feel some investment in our arts and culture (in my own case, being somewhat ‘bookish’). It was argued in a Wired essay, then spun into a book, that the internet would fundamentally change the market for culture; supply would meet demand more responsively and more dynamically. We had unmet needs stuck out in the “long tail”. The niche and otherwise obscure would reach the audiences who would appreciate it. In many ways it has. But the true implication of the long tail is that most cultural output is now the krill that the big conglomerate whales feed off. No individual artist living in the long tail will make any real money, but a corporation taking a 10% cut from the entire the long tail has a healthy return. We won’t be leaving the old gatekeepers behind any time soon and we still live under the tyranny of the lowest common denominator.

The new media landscape that has emerged has deeply frustrating shortcomings — even for increasingly well served readers. As Matthew Claxton observed in his newsletter on the phenomenon of the Brandon Sanderson kickstarter, if you go to Sanderson’s Amazon webpage for any of his books, the algorithmically generated recommendations put you at the bottom of a pit full of other Sanderson titles. The algorithm sends you to books you are likely to buy, which ultimately means bestsellers very similar to the bestseller you are already looking at. There is no effort to introduce you to new releases you might be interested in, or take you anywhere off the beaten path. Amazon has no interest in doing the things that bookseller enjoy doing, which must be utterly infuriating for booksellers who are learning the hard way just how irrelevant they are to the business of simply selling as many books as possible. Amazon could have been interesting if they weren’t so singularly focused on their algorithms.

What kind of bookseller would feel any pride in just putting the most obvious bestseller into the customer’s hands? One who only cared about making money, probably. One who had no investment in the treasure of discovery, certainly.

Let’s face it though: all of this talk is tiresome. The failures of our futurists is far less intriguing than the question of how we actually stumble upon our treasures of discovery. There is no reading list for life, and it is difficult to even talk seriously of a canon. It is more like we have inherited what is both a legacy and still growing, thriving enterprise. Both past and future works outpace us as more gets published then ever, and older works are rediscovered and re-evaluated. Every book listicle is a desperate attempt at navigating this reality. Engagement with this leviathan is no small feat: a book takes an unusual degree of engagement, in terms of time, concentration and intellectual commitment compared to most other narrative art forms.

To look back and wonder why I read any particular book is to confront free will itself. Something that the ideology of big tech pays some tribute to in all their talk of providing us with more “choice”. But it is reassuring to look back and find half a mystery and plenty of serendipity.

Some books I have read in large part because they were sat on a shelf before me, especially when I was younger. I read Thomas Harris’ counterfactual thriller that I found in the Welsh holiday cottage my family stayed at on the strength of the implied horror of blurb alone (what if…?). A similar story with Witches Abroad by Terry Pratchett, with the Josh Kirby cover art that drawing me in rather than the blurb. It was bound to happen sooner or later — there are enough copies of both Harris and Pratchett out there that maybe it was only a matter of time.

Sometimes it is someone else’s initiative that leads me over the threshold of the first chapter — I make a point of reading the books that friends and acquaintances recommend to me. HHhH by Laurent Binet. Rant by Chuck Palahniuk. Death at Intervals by Jose Saramago. Me Speak Pretty One Day by David Sideris. Cuckoo’s Egg by Cliff Stoll. Fifth Business by Robertson Davies. 4321 by Paul Auster. A Walk in the Woods by Bill Bryson. Recommendations removed from book marketing and publishing log-rolling, and read free form the usual burden of expectations. I really can’t think of any that have been remotely dissatisfying.

Then there are the recommendations of famous and celebrated writers. This is treacherous ground, with all the log-rolling, blurbing, favors, politics, and insufferably chummy niceness that ultimately muddies the waters. You rarely hear an author expressing dislike for another authors work, but any serious writer must have stronger opinions than they let on. A reader with a developed sense of taste should be discarding books they find weak or disagreeable, and I find it hard to believe a writer the stones to make strong creative decisions if they can’t abandon a dismal novel.

I can think of two writers whose recommendations I would trust. This isn’t necessarily correlated to my opinion of them as writers, just on how their recommendations seem to have worked out. 1. Neil Gaimain — who seems to have a consistent knack for championing and recommending great work in sci-fi, fantasy, and horror. He led me to Gene Wolfe, Susanna Clarke, and Jonathan Carroll. 2. Will Self — who, when he isn’t musing on the future of the novel, recommends some seriously interesting reads — The Strange Last Voyage of Donald Crowhurst by by Nicholas Tomalin and Ron Hall, and My Father and Myself by JR Ackerly. (I also need to get around to Riddly Walker by Russell Hoban, which he has been effusive about.)

It is worth noting that The Book of the New Sun by Gene Wolfe has a more complicated provenance than the Niel Gaiman recommendation. I have a vivid memory of being in high school, and reading a glossy paged coffee table book that must have been Science Fiction: The Illustrated Encyclopedia by John Clute. I pored longingly over the reproduced cover art and reading accompanying text. One book sounded particularly arresting. A singular reading experience where the reader is introduced to what is ostensibly a fantasy setting before it is gradually revealed through various clues and hints, that it is fact the Earth of the distant future as the Sun is dying. It was a quadrilogy, which back then seemed like an unthinkable commitment, even if I could track down a copy. Yet the memory of the book lodged itself deeply in my mind as something that I should read. Yet I didn’t memorize the author or title, so I really have no idea how I managed to rediscover it later.

And then there are the lists. There are so many book lists, and you might wonder what possible use they may have. One list in particular — 1001 Books to Read Before You Die — published in book form, left a particular impression on me because I quite seriously set about trying to read them all. I was young and the attempt could not have lasted more than a year. But this would have been how I discovered Philip Roth, David Foster Wallace, Ian McEwan, and many other “obvious” authors. I only got about a third of the way through A Suitable Boy by Vikram Seth, and I should probably get around to giving it another go. There was something incredibly empowering about just going in blind, irrespective of any perceived “difficulty” the book might have. I suspect it liberated me as a reader.

There have been other lists that have been useful. The New York Times Best of the Year list and the Booker prize shortlists have been worthwhile. (A Tale for the Time Being, bu Ruth Ozeki being a stand out discovery). Sometimes books just have reputations: 1984, A Brave New World, The Selfish Gene, and Sapiens. Sometimes they got mentioned repeatedly on the New York Times Book Review podcast, and the authors interview very well — so I had to pick up Educated by Tara Westover and Priestdaddy by Patricia Lockwood. Say what you like about the NYTBR, but having little interaction with the humanities side of academia, the highly networked worlds of genre and lit-fic, nor publishing more generally, they have been the best means of access available to me for the vicarious thrill of insider book-talk.

And who wrote those lists? Critics, you’d hope. Book reviews do in fact occasionally drive me toward reading a specific something. It was newspaper reviews that led me to Nothing Is True and Everything Is Possible by Peter Pomerantsev and Countdown to Zero Day by Kim Zetter. I’ve tried a few books on the strength of them getting an A on The Complete Review. And was given the impetus to read Aurora by a New Yorker profile of Kim Stanley Robinson from the past year. But disappointingly it seems like it is the general critical consensus that moves me to read something that any one given critic. I guess James Wood is responsible for bringing Karl Ove Knausgård and Elena Ferrante to our attention, and I have read books by both of them. But it wasn’t James Wood’s writing that sent me to the bookstore.

Unfortunately it seems that my need to read a book accumulates within me as mysteriously as the workings of any algorithm. I badly needed to get around to reading The Secret History by Donna Tartt and The Sparrow by Mary Doria Russell, but I couldn’t point to any one particular recommendation. And I read Gilead by Marilynne Robinson understanding the general critical acclaim it holds. It’s not unusual for me to read a book review and conclude that the book in question sure sounds great, only to file a mental note away in the overflowing mental filing cabinet.

And then there is the fact that one book can lead to another. I’ve spent a fair amount of time on various author’s Wikipedia pages trying to make sense of their influences. I’ve never anything like a systematic study, but I read Vance’s Tales of a Dying Earth because of Gene Wolfe, or and dipped into Dickens because of how much his novels have meant to Donna Tartt, among others. Authors may bridle at the question of where they get their ideas from, but tracking down their influences is fantastically easy. I could of course go about it the other way around and enroll in a “Great Books” course so I could convince myself that there is a coherent trajectory in literature that arrives at the present, but I think that’s better left as a vague aspiration.

A great deal of ink has been spilled in service of justifying extensive personal libraries of books that couldn’t possibly all be read in the owners lifetime. But their principal justification must be the ready richness of possibility that lies open before you when choosing the next book. We aren’t whales consuming books like krill. A book takes up residence in your inner life for days, weeks, months, or years. The cerebral furniture has to be arranged to accommodate the guest. As readers it doesn’t make sense to think about the “long tail” when the kinds of book I’m reading lived out there long before the internet came along. The long tail isn’t even a particularly meaningful concept then to readers like me except perhaps in reference to the way certain books can stay with us long after we’ve closed their covers.